Holding the thread in a tangled world

On love, migration, paradox, and the courage to see clearly

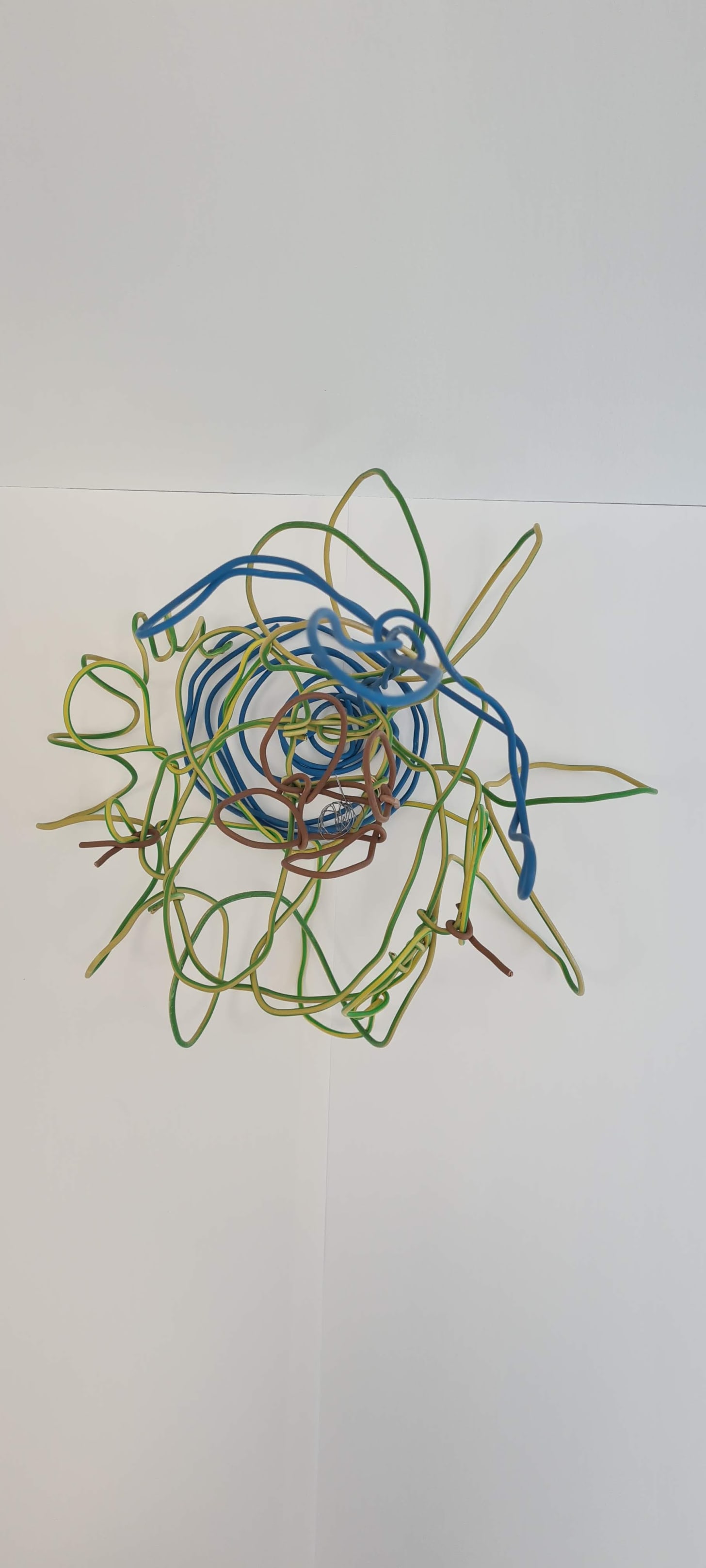

We live in a time when opinions harden faster than hearts. I’ve spent much of my life working in the field of migration, straddling cultures, and navigating the tension between loving all things and loving my neighbour as myself. It is not simple work. I try to be realistic as to when it’s possible in daily life. The world is tangled — in prejudice, politics, and pain — yet there are still threads of meaning we can hold onto. This piece is an attempt to follow one of those threads: to look honestly at complexity without losing compassion, and to ask what love requires of us now.

I listened to Trump’s ramblings at the United Nations. He seemed incapable of uttering a sentence without attributing great things to himself. He is Narcissus personified. Yet if he were more eloquent; if there was less navel-gazing; if he exaggerated less and told the truth more; if there were those things, he would be more credible – at least on some points.

He speaks of European nations going to hell for allowing too much migration from Islamic countries. I don’t believe they are going to hell; I believe much of the world is already there. But not only because of or even because of untempered migration. I have worked in this field for two decades, seen waves of government policies targeting less migration, better integration, more rigorous language and citizenship requirements, less obvious ethnic profiling, benefit scandals where governments have clearly discriminated against certain groups, increased poverty and societal division and sex abuse scandals made worse, some would say, because of fear of being labelled discriminatory.

My lived experience of being the daughter of an uneducated Chinese migrant and an uneducated English mother, living in the Netherlands for over twenty years and working in the field of migration, shows me that it’s complex. Complexity is no excuse for not trying to unravel some of the issues, but it does demand the capacity to hold paradox and to say ‘and and and’ often. I sense that this is too much to ask for many people nowadays.

It’s also important to note that complexity and simplicity are not opposites.

Simplicity is not the absence of difficulty or complexity. It is, however, a form of clarity that comes from living with the tangled realities of life. It’s what emerges when we hold paradox and choose carefully where to place our attention.

Having hosted many muslim migrants in my family home for the past decade and worked in a Dutch prison for migrants only, and having completed both a Masters and a Phd with migrants and professionals working with migrants (researching over the course of a decade), I do not speak from a place of ignorance.

I see real difficulty in integration. I see migrants whose backgrounds and cultures are premised on violence to achieve goals, rather than conversation, dialogue and compromise. I see extreme cultural and religious differences, which mean that problems are solved differently and values like loyalty and honour outweigh the values of individual freedom and choice. I see how my best friend, who is a Muslim refugee and single mother, struggles to keep one of her sons out of prison for drug dealing and violence and to protect her freedom-loving daughter from ever becoming the victim of an honour inspired crime. She continues to be a hard-working mother to her other two children, neither of whom have ever been in trouble with the police.

Complexity is a feature of society, of families and of individuals. And of nature, where various systems live alongside each other.

My PhD speaks of professionals and volunteers working with migrants who start off idealistic and become disillusioned. Others maintain idealism at a cost; others become more realistic; yet others step back altogether and become burnt out.

The system has its failings. Some people try to abuse systems, especially when they feel systems are not working for them. Others do it because they think they can and feel they owe nothing to no one. Not all societies have working tax laws. The rich benefit most. But there are some systems which care more for the poor than others. England is not the Netherlands is not Afghanistan is not Iraq is not Syria is not the Usa and so on and so forth.

People are on the whole better off in some cultures than others, especially if they are gay or women or poor. And whilst violence against women is a problem everywhere, I would rather be a woman in the Netherlands than in Iran or Pakistan. I would rather be gay in England than in Gaza. And I would rather not be in Gaza at all.

I am Christian and I live in a country where I can openly criticise the church. I am glad I am not a Christian in the USA, glad I am not a woman in Afghanistan and glad that I am not a Muslim anywhere. I believe in God and divinity and I also believe that I have a limited capacity for understanding God and divinity. I believe in the so-called transcendent and also believe it can be a powerful tool of the rich and educated to not do anything to attempt to change society. They use arguments like ‘things are as they should be’ or ‘everything is perfect as it is’. At the same time, others use their beliefs to justify their crimes and wars.

I believe the church has failed many. And I believe that without the church in Western Europe, or rather without a viable alternative to capitalism and greed and hatred, we are in even deeper trouble. I believe that Christianity can offer that alternative, and that it has been distorted by evangelical preachers and politicians who would use it for their own selfish and hateful ends. I also believe that the political left have failed. Rather than providing an alternative to the virulent right wing and conservative factions, they have bolstered their numbers by convincing those who might usually be tolerant, to employ excessive political correctness and censorship of anyone who disagrees with them. The right leads to fascism and the left to communism and I honestly don’t know which is worse. I desire none of those things.

Harking back to the past is not useful. Banging on about non-duality and oneness will not help much either. Pretending that migration is not a problem is to bury one’s head in the sand and that includes whether we are talking about the number of migrants, the type of migrants and the policies of inclusion of migrants into host societies and what host systems and populations do or don’t do. Pretending that all host populations have the economic, mental, physical, educational and social capital to absorb migrants into their midst is an illusion, especially given the unfair burden on the poor to do so.

According to the Bible:

The rich young man (Mark 10:17–31; Luke 18:18–30)

16Just then a man came up to Jesus and inquired, “Teacher, what good thing must I do to obtain eternal life?”

17“Why do you ask Me about what is good?” Jesus replied. “There is only One who is good. If you want to enter life, keep the commandments.”

18“Which ones?” the man asked.

Jesus answered, “‘Do not murder, do not commit adultery, do not steal, do not bear false witness, 19honor your father and mother, and love your neighbor as yourself.’f”

20“All these I have kept,” said the young man. “What do I still lack?”

21Jesus told him, “If you want to be perfect, go, sell your possessions and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven. Then come, follow Me.”

22When the young man heard this, he went away in sorrow, because he had great wealth.

23Then Jesus said to His disciples, “Truly I tell you, it is hard for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven. 24Again I tell you, it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God.”

For a Jew in the first century, heaven and eternal life were not necessarily some place we go when we die. They would likely have understood these concepts to mean living a life in line with God’s covenant NOW. We are talking about how God’s reign can come into being in the present time: how we transform life, relationships, justice and peace, in the here and now – not the hereafter. Obedience to the Torah was about living rightly before God now.

This does not solve the issue of complexity. And this doesn’t mean we should disregard notions of transcendence and awakening and enlightenment. It does mean, I believe, that we are called upon to look at what it is that is ours to do right now. Without blindfolding our eyes to reality. Without simplifying what cannot be simplified. Without reducing life down to the goodies and the baddies. And by being honest about the state of things and about the validity of other views and opinions, even if we don’t agree with them. The rich and educated do not share the same burden as the poor. The poor do not have the same safety net as the rich. Loving your neighbour might mean different things to both.

Choosing not to act right now is also an option. As is choosing prayer. But we need to know why we choose to act or not to act and to question our own arguments and reasons on a regular basis. Re-evaluating our values and priorities is a good step. Do you know what your highest values actually are? When things are complex, what is your go-to set of arguments or principles? Are you an ‘and-and’ type of person or a ‘yes, but’ one?

One of the values which has most served me in life is curiosity. When we have genuine curiosity we are open to learning from difference. This doesn’t imply that we agree with everything or that we don’t make choices. I believe we are more able to make informed choices when we embrace curiosity.

Be curious about the tensions and paradoxes in your own life. Note the contradictions and how you deal with ambiguity. There is no certainty in life. But there are threads. Perhaps your values and principles are the threads?

I’d love to hear your thoughts and will leave you with one of my favourite poems called The Way It Is, by William Stafford.

There’s a thread you follow. It goes among

things that change. But it doesn’t change.

People wonder about what you are pursuing.

You have to explain about the thread.

But it is hard for others to see.

While you hold it you can’t get lost.

Tragedies happen; people get hurt

or die; and you suffer and get old.

Nothing you do can stop time’s unfolding.

You don’t ever let go of the thread.